- Home

- Doug Swanson

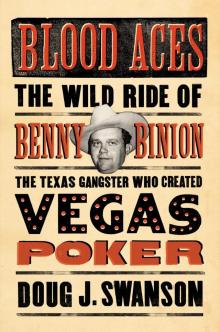

Blood Aces Page 16

Blood Aces Read online

Page 16

Not Binion. Kefauver’s lawyers had subpoenaed him, at which point he took off for his Montana ranch and stayed there, far from the reach of marshals hoping to serve papers. Further public exposure, he and his lawyers knew, could do him no good. The committee would not be hearing from the Cowboy. More than a few of Vegas’s mob-connected casino operators employed the same tactic. “The top brass of the underworld suddenly remembered long-forgotten relatives in distant lands,” wrote Hank Greenspun in the Las Vegas Sun.

One of those Nevadans who did appear, and seemed strangely happy about it, was William J. Moore, one of seven members of the state tax commission. He also owned a percentage of, and was an executive at, the Last Frontier resort and casino on the Strip, a position that paid him about $80,000 a year—ten times his state salary. He saw no inherent conflict in this setup, but did allow that such a role gave him a unique perspective on Las Vegas casino owners. He was asked if most of them were “of high integrity.”

“Well,” he answered, “it depends on how you describe ‘high integrity.’”

After a few more questions, he acknowledged that the gambling business in Nevada might be home to “a few more shady characters” than other commercial interests elsewhere.

As if to prove Moore’s point, Moe Sedway, once Bugsy Siegel’s number two man and now a vice president at the Flamingo, also appeared to testify, even though he wasn’t feeling so good. “I have had three major coronary thromboses,” he told the committee. “And I have had diarrhea for six weeks, and I have an ulcer, hemorrhoids, and an abscess on my upper intestines. I just got out of bed and I am loaded with drugs.” The senators nonetheless pushed ahead with their interrogation, and Sedway admitted that he had been in the gambling business in Las Vegas. Which, he reminded the committee, was perfectly legal, and probably not nearly as much fun or as lucrative as outsiders might imagine. “We don’t get as rich as you think we do. This is hard work,” Sedway testified.

Senator Tobey, the New Hampshire Republican who had elicited Virginia Hill’s claim to the fellatio gold medal, compared “scum of the earth” gamblers unfavorably to the honest people who “till the soil and make $2,000” back home in the Granite State. “They have got peace of mind and can look everybody in the eye,” he said of his constituents.

Sedway returned to the medical report. “Senator, you see what it got for me,” he responded. “Three coronaries and ulcers.”

Another witness, Wilbur Clark, developer and general manager of the Desert Inn, combined a faulty memory with a general obtuseness. This caused Tobey to blurt, in the middle of one ineffective exchange with Clark, “You have the most nebulous idea of your business I ever saw.”

Clark did admit that he had taken money from Moe Dalitz and his reputed gangster friends so he could finish building the Desert Inn. (These were funds that Dalitz got from, among others, the Republic Bank of Dallas via Binion.) Tobey then asked him, “Before you got in bed with crooks . . . didn’t you look into these birds at all?”

“Not too much,” Clark answered.

“You didn’t care where the money came from or how dirty or rotten,” Tobey said, “as long as you finished the building, is that it?”

“Well,” Clark said, “I wanted the building finished. I didn’t hear anything bad about those fellows.”

While the hearing had many such moments of bitter comedy, the committee failed to produce any kill shots. The session wrapped at day’s end with nothing in the way of blockbuster revelations. But the proceedings did cause Senator Tobey to brim with disgust. “What I have seen here today leaves me with a sense of outrage and righteous indignation,” he said after the session concluded. “I think it’s about time somebody got damn mad and told these people where to get off.”

That was possible, though unlikely. For as Tobey spoke, a block away on Fremont the colored lights glowed bright against the darkening sky. The Pioneer Club, the Nevada Club, the El Cortez: all had their beckoning signs ablaze. The Golden Nugget’s street-corner diadem sparkled as always. And on the sidewalks, the evening crowd of gamblers, their pockets thick with money to lose, flowed into the casinos.

• • •

Several months after Las Vegas, Kefauver took his traveling hearings to Los Angeles. Again the committee subpoenaed Binion, and once more he escaped to Montana. The senators brought in the lawman who knew all about the Cowboy, Lieutenant Butler of the Dallas police. Butler gave the senators Binion’s full criminal history, going back to his 1924 tire theft and continuing through the confrontations-by-proxy with Noble. Then Butler participated in a dramatic reading of the transcripts from Harold Shimley’s meeting with Noble in Dallas, the session he had recorded. Butler performed Noble’s part for the senators, while the committee’s chief investigator played the role of Shimley, with the principals’ many curse words deleted. And for dessert the Dallas lieutenant produced photographs of the smoking wreckage of the car in which Mildred Noble was smithereened. All in all, Butler provided the committee with a vivid portrait of Binion as a gangster of many talents, interests, and connections, and one whom the law had barely touched. This sort of exposure couldn’t have pleased the city fathers or the chamber of commerce. The next day the Dallas Morning News displayed a blaring front-page headline: “Crime Set-Up Here Blasted into the Open.”

Once the committee hearings were concluded, Kefauver—his eye on a possible run for the White House—wrote a book. He called it Crime in America, and it was a national best seller. Every book needs a villain, even ponderous tomes by ambitious politicians, and Kefauver had his: casinos controlled by the mob. “Hardened thugs,” he wrote of those who ran such a show. “Hoodlums, racketeers and the other inevitable parasites who spring up like weeds.” He wasn’t talking only about outlaws backing illicit games in warehouses and on piers while police took bribes and looked the other way. Kefauver believed legalized gambling was just as bad. It constituted an “economic blight,” the Tennessee senator insisted, and turned otherwise upright citizens into paupers, embezzlers, and slaves to depravity.

Las Vegas naturally emerged as this problem’s hot spot. “Nevada’s gambling centers have become headquarters for some of the nation’s worst mobsters,” he wrote. Unless something was done, he warned, “there is no weapon that can be used to keep the gamblers and their money out of politics.”

Kefauver even coined a term for this most pernicious of effects, the malign influence that infected a community and wreaked horrible destruction. He called it “Binionized.”

• • •

The senator’s publicity campaign was followed by even more public pressure on Binion. In the spring of 1951, the Texas House of Representatives convened a special committee to study organized crime in the state, and the Cowboy dwelled on the minds of those committee members as well. Herbert Noble’s presence only reinforced it. Noble testified that the price on his head had reached $50,000, and he laid that at Binion’s feet. “Benny never did like me too much,” he said, and repeated what he had told the papers back in Dallas: “I wouldn’t bow down to him.”

The house committee also subpoenaed California gangster Mickey Cohen, a short and growly ex-boxer with a florid history of bookmaking and embezzling. Several months before, he had been picked up by Texas Rangers in West Texas and strongly urged to take the next plane out. Cohen told the Rangers he was in the state looking to invest in oil exploration. “We’ve got nothing to hide,” he said. “We’re here to do business.”

Now Cohen ignored the legislators’ request to appear, saying he wasn’t in the mood to answer “some silly questions.” The committee had to settle for Warren Olney III of California’s Special Crime Study Commission on Organized Crime, who journeyed to Austin to deliver dire warnings about syndicate men buying oil wells. “What will happen if the gangsters get into the oil business?” Olney asked. “What will the industry look like if the slimy ways of the corruptionist and the violence of the

hoodlums becomes its day-to-day method of doing business?” This being the state legislature, no one mentioned that even without California mobsters, the Texas oil patch already came close to that.

Out in L.A., Cohen hardly talked like a rising petro-baron—although the Associated Press noted that he lived in a “radar-guarded home” in Brentwood, an exclusive neighborhood. Cohen claimed he hadn’t come to Texas to testify, because he couldn’t scrape together $168 for plane fare. Also, he was still under a contempt citation for failing to appear earlier, and was therefore subject to arrest as soon as he hit Austin. “I would be foolish to pay my way down there just to get pinched,” he said. “Tell them to drop dead.”

Cohen had other legal problems. The feds were about to charge him with tax evasion, and he faced an additional dispute concerning his car. A man who knew what it was like to be bombed and shot at, he owned a Cadillac custom-equipped with an armor-plated body and puncture-resistant tires with Seal-o-matic inner tubes. Only a bazooka could stop this rolling fortress—or a determined bureaucrat. The state of California informed Cohen that such a car needed a special permit, one exclusively reserved for law enforcement vehicles and currency-transport trucks, and it refused to grant him a personal waiver. Cohen sued the highway patrol, but a court rejected his pleadings. “It would be a fine state of affairs for people to be driving around in armored cars, promiscuously shooting at each other,” superior court judge W. Turney Fox ruled. The judge added that bullets might ricochet off such cars and wound innocent bystanders.

L.A.’s top mobster now had a Cadillac built like a tank that he needed to unload. It didn’t take much imagination to think of someone who could use such a vehicle. He picked up the phone and called Binion in Las Vegas, but Binion said no. Cohen—a man who knew how to work the angles—dialed Noble in Texas and offered the car to him for $12,000. But Cohen got no action there either. Recalled Noble, “I told him I didn’t want any part of him or his Cadillac.”

Perhaps Noble had developed a newly enhanced sense of fatalism, especially as his would-be killers grew more creative in their tactics. One day in early 1951, Noble climbed into the cabin of his single-engine Beechcraft on the dirt airstrip at his Denton County ranch. He pushed the starter switch, and the engine exploded. Pieces of hot metal sprayed in a hundred-yard radius. Noble was shaken but unhurt, because the plane’s firewall kept shrapnel from penetrating the cabin. The cause of the explosion stayed a mystery for six days, until Noble’s mechanic pulled the engine of another plane to see why it wouldn’t start. He found that two of the cylinders had been packed with nitroglycerin gel.

Noble had survived murder attempts numbers ten and eleven.

Still, he had to wonder how long his luck could last—certainly not forever. Noble prepaid his own funeral with a Dallas mortuary. The contract included a special clause stating the undertakers would pick up his body no matter where, when, or how he was killed.

• • •

If all the attention from various investigative committees worried Binion, he didn’t show it in his business affairs. In May 1951 “me and my son [Jack] went out to the Desert Inn,” he said. There they bought a drab and shuttered casino operation on Fremont Street that had once been owned by Moe Sedway, Davie Berman, and Bugsy Siegel. “It was called the Eldorado. It was closed. They’d fooled around there and they’d had an $870,000 tax loss. So I bought it for $160,000.”

Binion also took over the lease on the building, which included the Apache Hotel above the casino. He said the club would be remodeled top to bottom and would open soon with new management. His previous two casinos constituted mere warm-ups. This would be Binion’s grandest entry into the Las Vegas market. He would call it the Horseshoe.

A few days after the purchase, Binion applied for a casino license from the state tax commission, and the agency immediately rejected it. “I was getting some pressure put on me from somewhere,” he said. Like Mickey Cohen and his forbidden bulletproof Cadillac, Binion now owned a pricey asset he couldn’t legally operate.

The commissioners did not explain their decision, but it was clearly related to Binion’s racketeering past and his current legal problems in Texas. The glare of the Kefauver hearings had embarrassed the state, so tax commissioners adopted new policies designed to give the illusion of tough regulation. One of them prohibited licensed Nevada gamblers from owning a gambling establishment in another state, and Binion had been accused of doing that. Now, with his reputation and investment on the line in Las Vegas, Binion knew full well what had to happen next. It was time to start handing out money.

He had done it before. “I’ve bribed many a man in my day,” he once acknowledged. The right amount of cash distributed to the right people had always made the world work in Binion’s favor. He saw it as a mark of respect: “It takes a pretty good man to make you bribe him.”

Near the end of his life Binion was questioned about his spreading secret money around to influential officials. “And that’s always been your way?” he was asked.

“Yeah,” Binion answered.

“District attorneys?”

“Yeah.”

“Sheriffs?”

“Yeah.”

“Governors?”

“Yeah.”

“Lieutenant governors?”

“Well,” Binion said, “I don’t know of any lieutenant governors.”

The remains of Herbert Noble’s car after an ill-advised trip to the mailbox.

14

THE CAT’S LAST DAYS

They said he had nine lives. Damn good thing he didn’t have ten.

—BB

Neighbors had seen three men in a blue pickup truck rumbling up and down the dirt roads near the Noble ranch for several days. One man wore a red cap, another a pith helmet. They came, they lingered, they went. Nobody really got a good look at them, or paid them much notice. Then they were back, at night, unseen, digging a hole in front of Noble’s mailbox. There they buried nitroglycerin, dynamite, and blasting caps, and ran a wire to a new Delco car battery. When they had finished, one of them moved the truck down the road and out of sight. The other two hid in some brush sixty yards uphill from the mailbox, where they smoked cigarettes and waited for the sun to rise on August 7, 1951.

As morning came, Herbert Noble was in his sandstone ranch house less than a quarter mile away, preparing to head into town. He had been looking better lately. No longer gaunt and pale, Noble had turned ropy and tanned by working summer days around the ranch. His mental state, however, kept slipping its leash. The heavy drinking had continued, and he had, for reasons known only to him, demolished what was left of his family. His daughter, now eighteen, had gone against his wishes and married a young man from Colorado. For this, Noble drafted a new will, writing in pencil on a plain sheet of bonded paper, and cut her out of his estate. “There was nothing good enough for her at home (while Mildred and I were alive) so therefore naturally there could be nothing good enough for her here in case of my death,” he wrote. His holdings were worth about $1 million—including the Airmen’s Club, the eight-hundred-acre ranch, five airplanes, and 195 head of cattle—and from that he left $10 to his only child. Perhaps he had other uses for his money: police heard he had established a “revenge fund” with local toughs, money on deposit for vengeance should he actually be murdered.

Around eleven thirty that morning Noble left his house and got into his black Ford. He carried his gambler’s tools with him: his rifle, his cash—about $600—and his playing cards. As he drove from the house, he passed under overhanging post oaks, which gave little respite from the beating sun. North Texas was enduring yet another brutal string of 105-degree days. The crops withered in the fields, and the cows sought any scraps of shade they could find. In the downtown offices that had no air-conditioning, workers set blocks of ice in front of large fans. The men hidden in the brush, the ones watching for Noble now, felt the heat

too. But the prospect of earning $50,000 made it easier to endure.

Noble drove his car across the cattle guard and onto the dirt road that skirted his ranch, and if he noticed the freshly turned earth, he ignored it. He stopped at his mailbox. Noble liked getting the mail, one of the few happy side effects of his notoriety. The volume of letters picked up after each attempt to kill him. “I always get a lot after they try to get me,” he had said. “They write from all over the country. Some just want me to send money. But most of the letter writers wish me good luck.” These notes from strangers provided some small bit of solace for a man whose wife was dead and whose daughter was estranged. Maybe today’s post would have another good one or two. He reached for his mailbox.

• • •

Out in Las Vegas that same week, Virginia Hill paid a visit and cut a regal swath through town on the arm of former Binion bodyguard Russian Louie Strauss. “Boisterous, buxomy Ginny Hill,” the Review-Journal called her, “playmate of the syndicate big boys.”

Binion, meanwhile, immersed himself in the final days of preparation for the opening of the Horseshoe, which was to be a big step up from the typical Fremont Street grind joint. For one thing, it wouldn’t have bare floors sprinkled with sawdust. “I put the first carpet on the floor here in the Horseshoe that ever was downtown,” Binion said. “Everybody said that wasn’t no good, but it was.” Teddy Jane helped with the design because “I don’t know nothing about designing nothing.” Red emerged as the dominant color, western as the prevailing theme. Texas steer horns decorated the walls. This would be a place where high and low rollers alike could be comfortable, where the moneyed clients could strut about being rich, and the lesser ranks could pretend to be.

Blood Aces

Blood Aces