- Home

- Doug Swanson

Blood Aces

Blood Aces Read online

ALSO BY DOUG J. SWANSON

(Fiction)

Big Town

Dreamboat

96 Tears

Umbrella Man

House of Corrections

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2014

Copyright © 2014 by Doug J. Swanson

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Photograph credits

Special Collections, University Libraries, University of Nevada, Las Vegas: Pages x, 92, 104, 146, 232, 242, 254, 266, 276, 306

Collections of the Texas/Dallas History and Archives Division, Dallas Public Library: Pages 38, 48, 60, 70, 118, 134, 158, 196, 212

Courtesy of Fred Merrill Jr.: Pages 80, 186, 222

Las Vegas News Bureau: Page 298

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Swanson, Doug J., 1953–

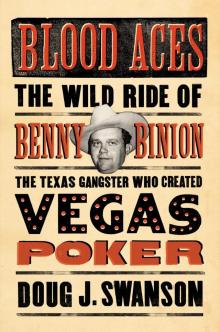

Blood aces : the wild ride of Benny Binion, the Texas gangster who created Vegas poker / Doug J. Swanson.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eBook ISBN 978-0-698-16350-8

1. Binion, Benny, 1904-1989. 2. Gangsters—Nevada—Las Vegas—Biography. 3. Gangsters—Texas—Biography. 4. Gamblers—Texas—Biography. 5. Gamblers—Nevada—Las Vegas—Biography. I. Title.

HV6452.N3S93 2014

364.1092—dc23

[B] 2013047860

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

Version_1

In Nevada, for a time, the lawyer, the editor, the banker, the chief desperado, the chief gambler and the saloon keeper occupied the same level in society, and it was the highest . . . To be a saloon keeper and kill a man was to be illustrious.

—Mark Twain, Roughing It

Contents

Also by Doug J. Swanson

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

PROLOGUE: THE HAPPY RACKETEER

PART ONE

THE ROLL OF THE DICE: 1904–1946

1.SNIDES AND DINKS: AN EDUCATION

2.THE BUMPER BEATER

3.PANCHO AND THE KLAN

4.GOOD FRIENDS AND A DEAD RIVAL

5.THE THUG CLUB

6.SHOOT-OUTS AND PAYOFFS

7.THE MOB WAR IS JOINED

8.“LIT OUT RUNNING”

PART TWO

DEATH AND TAXES: 1947–1953

9.MOBBED-UP PILGRIMS

10.TEXAS VS. VEGAS

11.“A KILL-CRAZY MAN”

12.“TEARS ROLLING DOWN THE MAN’S EYES”

13.THE BENNY BRAND GOES NATIONAL

14.THE CAT’S LAST DAYS

15.“THEY WAS ON THE TAKE”

16.“NO WAY TO DUCK”

17.THE GREAT BONANZA STAKEOUT

18.“WHACKED AROUND PRETTY GOOD”

PART THREE

THE RIDE BACK HOME: 1954–1989

19.THE FIREMAN GETS RELIGION

20.STRIPPERS AND STOOGES

21.CHARLIE, ELVIS, AND THE REVOLUTION

22.ANOTHER ONE BLOWS UP

23.HEROIN AND THE HIT MAN

24.U-TURN AT THE GATES OF HEAVEN

25.“THEY DO THINGS LIKE THAT”

26.HAPPY BIRTHDAY, DEAR BENNY

EPILOGUE: BACK IN THE SADDLE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

Benny Binion (right) at his peak, with the actor Chill Wills (center) and an unidentified man outside the Horseshoe Club in downtown Las Vegas.

Prologue

THE HAPPY RACKETEER

Do your enemies before they do you.

—Benny Binion

The three men were hired killers, not ditchdiggers, and after weeks of ceaseless heat with no rain, the ground was like concrete. They labored to shovel a small hole into a dirt road that cut through Texas ranchland. A weak sliver of moon hung low, the night so dark the grunting and sweating men could hardly see their hands. It was early August 1951, and they were preparing yet another attempt to murder a gambling boss named Herbert Noble.

Eleven previous tries—bombs that didn’t go off, shots that missed—had failed. But this time, the men told themselves, would be different. No more firing wildly through upstairs windows, no more harebrained schemes like packing airplane engines with explosives. This time they had patience and a plan. They also had the promise of a big payday, for the bounty on Noble had increased tenfold.

Now the hole was big enough. The men carefully nestled several sticks of dynamite next to some packs of nitroglycerin gel. They put blasting caps in, too, then covered it all with dirt. A wire ran from the blasting caps to a Delco car battery hidden in some roadside brush. Another wire extended from the battery up a small hill to a clearing behind some bushes. There they waited in the dark.

At last the sky paled, a slight breeze stirred, and birds began to sing. The sun rose—welcome at first, until it climbed higher and began its nasty beating from a cloudless sky. The men crouched in ragged shade and scanned the emptiness of the rolling landscape. There were clusters of scrub oaks scattered across the crisp, dry pastures. A barbed-wire fence, strung on cedar posts, lined the road. Minutes dragged by, hours. Finally, about eleven thirty that morning, they saw Noble’s black 1950 Ford.

Noble stopped the car at the head of the driveway to his Diamond M Ranch, named for his beloved wife, Mildred, who had been blown apart by bumbling assassins two years before. As he reached for his mailbox, one of the hidden men gripped the insulated copper wire that ran from the car battery. All he had to do now was touch it to the barbed-wire fence, grounding the connection, and let the bomb do its work. Then the three could collect $50,000 in blood money—this in a state where you could have just about anybody killed for a couple of thousand.

It represented a high price for a rubout. But the man who everyone—police, criminals, even Noble himself—believed had bankrolled this particular job could easily afford it. He lived now in Las Vegas, Nevada, where he was, this very morning, putting the final touches on his greatest gambling palace ever. He was Benny Binion, one of the most feared and successful racketeers of his day.

• • •

Not that he looked it. At this stage of his life, Binion was a moonfaced, portly middle-aged casino owner in cowboy boots and a cowboy hat, with a couple of loaded handguns in his pockets and another in his boot. “A big, beefy, jovial sort of fellow,” one fawning writer called him. People sai

d he was practically illiterate, a notion he did little to dispute. Binion had thin, uncombed hair and rumpled, ill-fitting clothes. He talked with a twang that needed oil, displayed a grin that seemed fresh off the farm, and shook when he laughed. One of his sons said he looked like a happy baby with wrinkles. “You couldn’t keep from liking him,” said a friend and associate, R. D. Matthews.

Binion had long resembled a doughy rural-route cherub, at least until he decided he wanted somebody dead, which had happened with some frequency. Then his grin fell away and his darting blue eyes went hard. “No one in his right mind,” the great poker player Doyle Brunson once said, “messed with Benny Binion.”

Occasionally Binion did his own killing, as he phrased it, and other times he delegated the job to his homicidal staff. Through it all, his dim, country-cousin bit served as a convenient mask. In truth Binion combined native intelligence, shrewd calculation, and cold-blooded application. He was a rube savant who fueled his rise by manipulating, charming, intimidating, and murdering as needed, with more than a few pauses for self-mythologizing. “There’s been a lot of them wanted to kill me,” he once said, “but they missed.”

He had started his criminal career in Texas, and soon no one there could top his power and sway. Binion ruled his Lone Star kingdom for a decade, as dollars flowed and blood ran. From his Dallas perch, he embodied the American dream, if one dreamed of an empire of vice. Then he moved to Las Vegas as the modern version of that city was being born. There he helped lead a wave of dirty money and dangerous men who transformed it from a desert watering hole to the century’s great gambling capital. Binion employed timing, temperament, and access to loads of cash to be one of Las Vegas’s vital new pioneers, a cowboy counterpart to the syndicates from the coasts. He brought high-stakes dice games. He created the World Series of Poker too. As much as anyone, Binion made Vegas a mecca for high rollers. Before he was done, they were putting up a statue of him and thousands were chanting his name.

The nation’s history is packed with legendary outlaws. But none of them can match Binion’s wild, bloody, and wholly American journey. He rubbed shoulders with some of his era’s biggest celebrities and its richest men. He did business with—and counted as friends—the most notorious of mobsters. He was chased and nearly destroyed by the most powerful figures of his time, from J. Edgar Hoover to the president of the United States.

It is still said in Las Vegas that you can’t understand the town without understanding Binion, that he put the gamble in Vegas, that he ignited a worldwide revolution in poker. All of it is true, but his story looms larger and wider than that.

There is simply no one who went from murderous street thug to domineering crime boss to revered businessman to civic treasure like Benny Binion. No one comes close. This is how he did it.

PART

ONE

THE ROLL OF THE DICE

1904–1946

Lester Ben Binion at the age of four.

1

SNIDES AND DINKS:

AN EDUCATION

We was all grifters in those days. All we had was grift sense.

—BB

He came from nothing, or the nearest thing to it. The son of Alma Willie and Lonnie Lee Binion, he was born in Pilot Grove, Texas, on November 20, 1904. The Binions lived in a drafty clapboard house, where they sweated through the furnace heat of rainless North Texas summers and shivered in the winter as the north wind whipped over the Red River. They weren’t the poorest people around, but hardly the richest, and the family took in boarders when money was tight. At night, in shadowed rooms lit by candles and flickering oil lamps, the paying guests could hear endless coughing through the walls: young Lester Ben Binion, a round-faced boy with blond girlish curls, had pneumonia five times before he was five. As he lay in his bed, gripped by fever and chills, he sometimes crept perilously close to death. His sickliness may have been his first great stroke of luck.

Like dozens of small towns scattered across the rolling blackland prairie, this one was destined to vanish. Originally called Lick Skillet, it was a place of bloodshed, hard living, and ill fortune from its founding. Even after being christened with a more pastoral name, Pilot Grove scratched by as a cotton and cattle town, as close to Oklahoma as to Dallas, and a long way from anywhere. Its main street, part of an old stagecoach route, was a dirt road that gave up clouds of gray dust or bogged carriage wheels in mud, depending on the misery of the season.

Many of the town’s early settlers—the Binions among them—had arrived on wagons after the Civil War, and some brought the war’s vestigial agonies with them. Thick woods nearby, which had been a perfect hideout for war deserters and other fugitives, now teemed with unreconstructed Confederates nursing their bitterness. Newcomers tended to be Union sympathizers, and it made for a deadly mix. There were raids and ambushes from both sides, and gunfights in broad daylight. The town doctor treated one of the wounded rebels, an act of mercy that so enraged one of the unionists that he murdered the doctor. One frosty morning in 1871, the leader of the Union League stepped from his house to retrieve some firewood when two rebels, who had been hiding in trees all night, shot him dead.

A few good, relatively peaceful years boosted the town’s population to about two hundred, then came the withering. Pilot Grove’s post office was shuttered the year Ben was born. When he was four, on a May evening, a line of boiling storms rolled in from the west with a blast of wind and cascades of thunder that shook the walls. Just after dark, a lightning bolt struck Sloan’s general store, and the wooden building caught fire. Flames, whipped by the gales of the storm, leaped to the barbershop, the drugstore, the blacksmith’s barn, and another general store. Townspeople could do little more than watch in escalating desperation, with firelight dancing over horrified faces. Pilot Grove had no fire department, no fire wagon, no way even to spray water on the flames. At sunrise the town’s commercial district lay in char and ashes, with only the hotel and one store standing.

Disaster was heaped upon catastrophe as drought and plunging prices destroyed the cotton market. Still, a farmer who had a mule and a plow could coax a living from the land around Pilot Grove, but not much of one. The Binions were not exactly noble sons of the earth, which worked to their advantage. One of Ben’s grandfathers had operated a saloon. The other also owned some land, but he rented it out. One summer day, hot enough to force a retreat to a canopy of oak trees, young Ben crouched in the shade and watched as his grandfather leased acreage to a man named Kato. When their business was done, as Kato walked away, Ben’s grandfather decided it was time for a lesson. “That’s the best farmer I know,” he said.

The boy stared. His grandfather pointed to the worn patches on the seat of the farmer’s ragged overalls. “You see where his so-and-so’s been sticking out there?” he asked.

“Yeah,” Ben answered.

“Don’t ever stick a plow in the ground.”

End of lesson, and one that had apparently taken hold much earlier with Ben’s father, who did not favor tending crops or any other kind of steady work. Lonnie Lee Binion listed his occupation as stockman, which meant he spent most of his time as a wandering horse trader. When he did come home, he hit the bottle. “Kind of a wild man,” his son recalled. “Kind of a drunk.” Such qualities did not make for a father given to softheaded sentiment, even when considering a sick child. One day Lonnie Lee looked at the boy, turned to his wife, and said, “Well, he going to die anyhow. So I’m just going to take him with me.”

Off they rode on two mounts, he and his father, out of Pilot Grove and the drudgery of its cotton and sorghum fields, and into a world of renegades, grifters, hustlers, and highwaymen. Ben, at the age of ten, had spent little time in any classroom; after four years he was still in the second grade. This would be a different sort of school, and it gave him his life.

“There’s more than one kind of education,” Binion said decades later, “an

d maybe I prefer the one I got.”

• • •

In much of America, the early 1900s marked the Progressive Era, a time of economic growth, social gains, industrial expansion, and technological leaps. But not so much in Texas. With a few notable urban exceptions, the state remained remote, parochial, and in parts lawless. Barely a generation had passed since the Indian wars had ceased. A hurricane wiped away the state’s most cosmopolitan city, Galveston, in 1900. In all its great sweep, Texas had little in the way of heavy industry, and its only semblance of intellectual life was sequestered at a university or two, where it was regarded with suspicion, if not hostility. By even the most generous of estimates, Texas at the dawn of the twentieth century remained a full fifty years behind mainstream American development. Although patches of it had been conquered and settled in the previous decades, the vast land remained essentially unchanged. So, for the most part, did its people.

The roaders, as roving livestock merchants were called, had likewise failed to evolve much from the frontier days. Young Ben Binion—sometimes in the company of his father, sometimes not—became one of them. The traders with their strings of horses made their way over the rough trails and dirt roads of the Lone Star outback in clouds of dust and flies. They carried guns and lived out of wagons. In Europe, the Great War had started. The Panama Canal opened, and commercial air traffic began in this country. In the cities—even those in Texas—buildings were lit with electricity. But the roaders cooked their meals over open fires, bathed in shallow brown creeks, and moved from camp to camp, from settlement to farm to town, in search of more horseflesh deals.

Small hardscrabble farms of this time and place had little in the way of mechanization; mules or horses pulled the plows and wagons. Rare was the farmer who owned a tractor, rarer still one who had a truck or car. The horse trader, therefore, peddled an essential element of the farmer’s survival. At times the stock was swapped straight up, horse for horse. Usually, though, the farmer had to throw in “boot”—food, tobacco, or occasionally cash—to make the trade.

Blood Aces

Blood Aces