- Home

- Doug Swanson

Blood Aces Page 2

Blood Aces Read online

Page 2

Young Ben Binion watched and learned. He proved especially adept at gauging a horse’s age by inspecting its teeth. “I was real good at it,” he said decades later, talking to a historian. “All them old guys I worked for, they let me do the mouthing of the mules, and horses, and everything, you see, while they was trading and talking.” When not mouthing the mules, Ben absorbed the primary lesson of this marketplace: how to deal, how to cheat, and how to avoid being cheated. The assumption was that if someone wanted to trade away a horse, that horse was defective. Everyone was out for the swindle, and he who swindled best, won.

“They had heaves in them days. They were wind-broke horses, and balkies,” Binion said, referring to equine respiratory disease. “They called them snides and dinks. So you’d have to give ’em medicine to shut the heaves down.” This medicine provided no cure; it merely masked the symptoms long enough to close a trade. There were other tried-and-true ways to hide infirmities. Wads of cotton, soaked in chloroform and stuffed in the nostrils of dangerously excitable horses, made them temporarily docile. Pebbles in the ear of a sluggard would transform it, for a while, into a frisky and energetic creature, prancing and shaking its head as if it were raring to go. A “sweeney” horse—one that had been so overworked that its muscles under the harness had collapsed—could be made to look instantly vibrant if the trader punctured the skin over the sagging parts and blew in air through a goose quill. “Some men were smart enough to detect it,” Binion said, “and some weren’t.”

A ditty of the era, “The Horse Trader’s Song,” captured the attitude of those on the tactics’ receiving end:

It’s do you know those horse traders,

It’s do you know their plan?

Their plan is for to snide you

And git whatever they can.

Sometimes the deception could be achieved simply through strategic staging. “Get a horse up on a kind of a high place, and get the man down on a low place, you know,” Binion said. “And if he had anything wrong with him, try to keep that turned away from the guy.” Not all valuable knowledge imparted to the boy had strictly to do with animals. “I learned a lot about people.”

He became the man of the family, returning home now and then, a twelve-year-old grown-up. “He was an adult his whole life,” his sister, Dorothy, once said. Trading balky livestock was no way to become wealthy, but it did pay for the family’s groceries. When not hustling horses, he sometimes hauled fuel for an uncle’s syrup mill in Pilot Grove. Then, back on the road, he found an even better way to make money.

• • •

In those years, nearly every county seat hosted monthly events known as trades days. Named for their spot on the calendar—First Monday, First Tuesday, and so on—trades days usually coincided with the arrival of the circuit-riding judge. They served as a combination of county fair, open-air market, and gathering of the rural tribes. For farmers and others in the hinterlands, they provided a monthly relief from lives of privation and isolation. The sodbusters and their families streamed in from the countryside, wagons loaded with the crops they intended to barter for dry goods and assorted services. Itinerant merchants brought everything from axle grease to snake oil. There were evangelists, buskers, blacksmiths, and rainmakers. On a typical First Monday in Dallas, the streets adjacent to the courthouse were nearly impassable with the crush of horses, wagons, and people. The air smelled of hay, manure, and sweat.

And down Houston Street, C. D. Tatum’s Bar beckoned to men in overalls and felt hats. Trades days offered opportunities for recreation not available back on the farm. One might buy whiskey, smokes, or a woman, and watch dogfights, cockfights, or human fights. Into this licentious mix came the traveling gamblers, who moved from town to town, hunting suckers at trades days like predators stalking a herd. Men could be found in the alleys and side streets, or in the wagon yards at night, rolling dice on a blanket spread over the dirt, or playing cards by lanterns and firelight. Teenage Ben Binion was right there with them.

“I kind of got in with the more of a gambling type of guy, you know, the—you might say the road gamblers,” he said. “And then I’d go around with them, you know, and I’d do little things for them. And they’d give me a little money, kind of kept me going . . . They was all pretty good men.”

Here he served his apprenticeship. “First, I learned to play poker,” Binion recalled. “And everybody had his little way of doing something to the cards, and all this, that and the other.” Marking cards and crimping them were among the most popular ways to gain an advantage. “So I wasn’t too long on wising up to that . . . All this time I’m kind of learning about gambling from these guys.”

Soon he became a “steer man,” a recruiter who wandered the trades-day towns after dark, hooking customers for the big game around the corner. “I just hustled, never did work,” he said. He stayed on the lookout for someone with money to lose, but also searched for something more. Binion described his mark: “What I think makes a player is somebody with a lot of energy. Like if one of them kind of fellows come to town at night, you know, he’s kind of a nervous type, and he had to have some outlet, you know, couldn’t just go to bed like a ordinary person.”

Even as a young man, Binion didn’t gamble much. “I was never able to play anything, dice or cards or anything, myself. I was never a real good poker player,” he said. Instead, he was a partner—however junior—to the game’s operators. “Fact of business, from a early age, I was always kind of in, and just kind of on the top end of it.” Here he received his most valuable of lessons: that hot streaks come and go, that one good roll could feed a man for weeks and a bad one could destroy him. But the properly run house always turns a profit.

• • •

The youthful Ben became known more rakishly as Benny Binion about the time he headed for El Paso, in far West Texas, around the age of eighteen. He went to El Paso because he had cousins there, but he soon discovered he had landed in a place well suited to his abilities and instincts. This was one of the country’s great snake pits of smuggling.

Under Prohibition, liquor was then illegal in El Paso, as in the rest of the country. But bootleg booze—and drugs—proved far easier to obtain along the border than many other places. All the Texas importer had to do was cross the muddy, shallow Rio Grande into rollicking Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, load his wagon with whiskey, and bring it back home to sell. In the process he had to evade bands of Mexican thieves on one side of the river, and roving hijackers and American agents on the other. A fevered newspaper dispatch from El Paso described the face-off: “The brains of Texas Rangers and an army of federal customs officials and narcotic and liquor agents” were “pitted against the endless ingenuity of international smugglers in as thrilling a battle for supremacy as the romantic and adventurous days of a half century ago ever knew.” The story added that “this battle of wits” makes “the plots of red-blooded fictionists seem dull and old fashioned.” Trains of pack mules bearing contraband champagne had been captured. A young man “disguised as a cripple” was caught hiding cocaine in his hollowed-out crutches. Other smugglers used the chest cavities of corpses, en route to their own funerals, to transport caches of morphine and opium.

The Texas Rangers, assigned by the governor to patrol the border, routinely fired on bands of so-called rumrunners, and the runners fired back. Many of the gunfights took place on or around Cordova Island, near Juárez. This was not an island at all, but a brushy 385-acre finger of Mexico poking into the American side of the Rio Grande, where the two sides took turns ambushing each other. A news report told of a typical encounter—a “pitched battle”—along the river: “Descending upon the rum-runners in speeding automobiles, the patrolmen mounted a fence near the Rio Grande. They were met with a fusillade of bullets from the rum-runners’ rifles. The fire was returned and two of the smugglers were seen to fall to the ground.”

Binion tried lawful work in El Paso, but�

�in this atmosphere—it didn’t stick. “He had a gravel wagon and some mules, and was spreading gravel on this parking lot for Model T Fords,” his son Jack recounted. “He figured out they were bootlegging out of the booth where you paid for your parking.” He procured his own stock of contraband whiskey. “And he’d come down and go to work about five in the evening. Some guy would come up and say he was looking for Joe, and Benny Binion would say, ‘I’ll take care of you,’ and sell them his own liquor.”

Binion was arrested for bootlegging at least once in El Paso and put in jail. “They made him a trusty,” Jack said. “One day they told him to go get judge so-and-so some liquor out of the evidence vault . . . Benny Binion went and made an imprint of the key. Sent it out and had a key made. Then he got the jailer drunk, and when the jailer went to sleep, he called up a friend with a truck, got some of the other trusties to help load it, and stole a truckload of liquor right out of the jail.”

Like many Binion family stories, this one has a deceptively winking, comical aspect to it. County records are gone, and all that remains are family recollections, which tend to paint Binion as an enterprising scamp with a heart of gold. “My dad was a happy, jolly man,” recalled his daughter Brenda Binion Michael. But Benny Binion roamed El Paso as a young gun in a violent place, launching a professional career of brutal strategies and heartless expediency. He once summed up this life with the declaration “I wasn’t to be fucked with.” When asked many years later about his El Paso days, Binion turned alternately boastful and reticent. “Hell, I didn’t need a bodyguard or a chaperone or guide or nothing,” he said. “I got to be known pretty fast.”

Known doing what? “Well,” he answered, “I’d just as soon not tell it.”

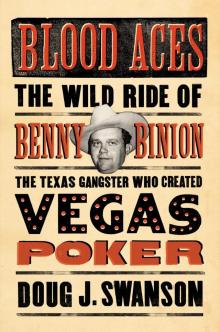

Teenage Ben Binion in a family photo.

2

THE BUMPER BEATER

I try to keep anybody from doing anything to me where it’ll cause any trouble. But if anybody does anything to me, he’s got trouble.

—BB

For reasons now lost, Binion felt a sudden urge to leave El Paso. He turned up six hundred miles away, in Dallas, at the age of nineteen. As he rolled into town, he no longer looked like a yokel who spent days on a horse, riding the range. This Benny Binion wore a dark suit, shiny cap-toed shoes, and a snap-brim fedora with a striped hatband. He stood a shade under six feet, and had a hustler’s glimmer in his eye. As he was to learn soon, the city offered wondrous opportunity for a young man with a spirit of larceny underpinned by a mind for business. “Dallas,” he said, “is one of the best towns that I ever seen.”

It is perhaps unfair to say that the city where Binion had come to make his bones was founded by a lunatic gunslinger. The man who first settled Dallas was, when he arrived in North Texas, still a few decades away from shooting someone or going crazy. Nor is it accurate to note that the pioneers who ran Dallas knew instantly how to make money from vice. That took them at least five years to figure out.

The city was born in 1841, when Texas was still a republic. It began as a simple trading post on a low, windy bluff along the narrow, murky, and sluggish Trinity River. John Neely Bryan, a Tennessee lawyer and occasional Indian trader, made camp on the bluff with a tent, a shaggy dog named Tubby, and pipe dreams of a thriving river port. Someone—maybe Bryan, maybe a settler who trickled in behind him—decided to call it Dallas. To this day, nobody knows why.

Bryan soon married and built a log cabin for his bride. Others homesteaded too, and within a few years a town had risen, with Bryan as its first postmaster. By 1846, Dallas had impaneled its first grand jury, which promptly indicted fifty-one men for gambling at the local saloon. They had been betting on, among other things, rat and badger fights. When it came time for trial, there weren’t enough unindicted citizens to fill a jury. At the courthouse—a ten-by-ten log structure—the solution was quickly engineered: After the first gambler was found guilty, he took his turn on the jury, and the juror he replaced stepped down to be tried. Next gambler, same story. Eventually all fifty-one convicted each other and fined themselves $10 apiece.

The Trinity River proved to be too full of snags and sandbars for boats to travel three hundred miles north to Dallas from the Gulf of Mexico. One paddle wheeler eventually made it all the way from Galveston, but the journey took a year and four days. So much for Bryan’s vision of a port. Nonetheless, by 1850, Dallas boasted a population approaching five hundred. Within a few more years, it had a hotel, a sawmill, and a carriage factory. Soon a high school was established, and the first circus—featuring one live elephant—came to town in 1859. A city was taking shape.

The great founder Bryan did not fare so well. He suffered from the effects of cholera, heavy drinking, and an erratic disposition, and wandered away from the town he founded. After a year of prospecting for gold in California failed to yield a fortune, Bryan returned to Dallas and shot a man who insulted his wife. Poor health and mental turbulence ended a brief stretch in the Confederate army. In 1877 he was admitted to the State Lunatic Asylum in Austin. He died there seven months later, and was buried in an unmarked grave.

A few decades after Bryan’s death, Dallas considered itself the commercial capital of Texas, “a city of skyscrapers, resounding with the roar of trade,” in one booster’s assessment. Its population exceeded 150,000 by the mid-1920s, and the twenty-nine-story Magnolia Building, the tallest in the South, had been finished downtown. Already a banking center, Dallas had a growing university, a branch of the Federal Reserve, and a major Ford plant. Conservative and insistently religious from the outset, the city presented itself as a prosperous, upright metropolis of unforgiving rectitude, the type of place where a man who stole a pearl necklace, a watch, and $21 in cash was sentenced to death. Yet for many years it also had—and openly tolerated—a place called Frogtown.

Also known as the Reservation, Frogtown looked like any other collection of hardware stores and barbershops on the edge of the central business district, but for the nearly naked young women draped in the doorways, calling to customers. Frogtown functioned as a freely accepted and legally sanctioned zone—via an ordinance by the city commission—for whorehouses. There were, by some estimates, four hundred women working there, though it was by no means the only place to find a prostitute in Dallas. One successful brothel operated out of a city-owned skating rink in Fair Park.

Police patrolled the Reservation; they simply didn’t arrest prostitutes, although one chief ordered the brothels to place screens over their doors so that activities inside weren’t visible from the street. The district attracted the notice of, among others, the appropriately named J. T. Upchurch, a preacher who had founded the Berachah Rescue Home for Fallen Girls, and who recorded his outrage in his periodical, the Purity Journal. “Some hundreds of girls are kept in this district as Slaves; Slaves to Lust, Licentiousness and Debauchery,” he wrote. “They are there to gratify the unbridled passion of beastly men and to produce a few grimy, bloody dollars for the lords of the underworld.” Upchurch may have been right about unbridled passion, but he misfired with his attack on the lords of the underworld. Even an outsider in town for a week could see the error in that.

In 1911 a Presbyterian minister from New York, Charles Stelzle, came to Dallas for a speaking engagement. A follower of the Social Gospel movement, which applied Christian ethics to social problems, Stelzle spent a few days wandering the city and taking notes. Then, before an audience of fifteen hundred at the Dallas downtown opera house—an ornate forum meant to replicate the great theatrical palaces of Europe—Stelzle condemned not just the fleshpots of Frogtown, but their landlords too. “What about the men who rent those houses?” Stelzle asked. “Do you know who owns them?” The crowd began to stir. “I have made investigation. Some are owned by some of your first citizens.” He thundered, “I have their names!”

The audience urged him on, but Stelzle refused to divulge his list. “Not on your life,” he demurred, and changed the subj

ect. It was an open secret anyway. Chief among the brothel property owners was Dr. W. W. Samuell, a prominent physician and civic benefactor for whom a street, a park, and a high school in Dallas would come to be named.

Many people knew about this, but relatively few of them cared. After all, a Reservation landowner could easily net $50,000 a year on his investment. For Dallas, it was a matter of vigorous free enterprise trumping moral concerns. The city took much the same approach to whiskey.

• • •

July 12, 1929, was another day of hard summer heat in downtown Dallas: the midday sun like a blister in the washed blue sky, the air fouled with fumes from rattling Fords and Packards. Pedestrians cast small, hard shadows as they moved past the movie theater marquees. The Palace was showing the Marx Brothers in The Cocoanuts. And at the Melba—its slogan was “Always Healthfully Cool”—Dolores Costello “and a cast of 10,000” appeared in Noah’s Ark, a forgettable love story at sea. Matinee admission, 35 cents.

Streetcar bells clanged, and the Manhattan Café on Main Street was packed at lunchtime. The clock hanging over the sidewalk at the Dallas Trust and Savings Bank showed straight-up noon. Down the block, on the steps of the county courthouse, a crowd had gathered. A celebratory air prevailed as Sheriff Hal Hood prepared to order the destruction of five thousand gallons of forbidden whiskey. Hood, the latest in a considerable line of hapless county lawmen, had been humiliated into the act.

Prohibition had long been the law of the land, even longer in Dallas, which voted to ban liquor three years before the Eighteenth Amendment took effect. The local dry forces took pride in declaring they had shuttered more than 200 saloons and 150 stills. Yet whiskey flowed freely in many parts of the city, where drinks were as easy to acquire as whores had been in Frogtown. Police conducted the occasional crackdown, and sometimes made arrests, but such actions usually served merely to generate publicity and payoffs. So lax was enforcement that Collier’s magazine, a national publication out of New York, dispatched a writer to investigate. He found six places in a two-block stretch of downtown Dallas where he could buy liquor. “Regardless of its registered attitude in favor of strict enforcement of dry laws,” he wrote, “I know of no town more bold in its violation of them.”

Blood Aces

Blood Aces