- Home

- Doug Swanson

Blood Aces Page 3

Blood Aces Read online

Page 3

Pretending to be outraged, Sheriff Hood immediately ordered his deputies to commence a series of raids. Like drinkers and magazine writers, his men had no trouble finding saloons. The basements of any number of downtown buildings had them—bare-bones affairs in many cases, with hand-lettered signs and hard chairs. Men drank from unlabeled amber bottles and rolled dice on the concrete floor between tiny, dark pools of tobacco spittle. Hood’s deputies moved in and seized hundreds of barrels of bootleg liquor.

Now the contraband would be dumped and order restored as the city cheered. By noon, the spectators overflowed the courthouse steps. Deputies removed their coats, revealing their galluses and holstered sidearms. Ladies from the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, wearing long skirts and carrying Bibles, fanned themselves, watched, and prayed. Some sang hymns and gave thanks to God for this glorious occasion.

The deputies tapped the first barrel, then another. The kegs were turned on their sides and tilted at the edge of the curb, and the whiskey gurgled out. As bystanders pitched in, even more liquor splashed into the gutter. Vapors rose in the heat, the scent of sin ascending heavenward.

This was proving to be a beautiful and triumphant moment for Sheriff Hood, at least until someone lit a match and tossed it into the gutter. First came a great whoosh, then an eruption of blue flames. In seconds, downtown Dallas had a river of fire rolling down Main Street. There were screams and scrambles. The fire extended for several blocks, “a long blue blaze of intense heat,” in the words of one witness. The flames spread to the lot of the Fishburn Motor Company, and when at last the fire department arrived, more than twenty cars had been damaged or destroyed. Next time, vowed the embarrassed Hood, his men would pour sufficient water into the gutter along with the liquor.

Few believed there would be a next time. By the following week, the illegal saloons were back in business and as crowded as usual. Any man stepping off a streetcar in downtown Dallas could buy liquor on the corner. In fact, he could buy it from someone working for or with Benny Binion, who was just beginning the process of making himself into a racketeer.

• • •

For someone without an education, and not inclined to steady labor, bootlegging offered one of the best paths to riches. A 1925 study had shown the annual earnings of a Dallas bootlegger to be about $36,000, far surpassing that of many doctors and bank presidents. The bootlegger may have exceeded those men in prestige as well. To a legion of drinkers, who believed the government and the bluenoses had conspired against them, the whiskey man represented a blend of public servant and folk hero.

Binion, using an ever-expanding network of friends and family, quickly established himself as a middleman in the liquor trade, the modern-day equivalent of an importer-distributor. He staked out a commercial terrain between the hidden still in the country and the undercover saloon in town. Binion’s crew arranged for, transported, and protected the inventory, while tacking on a sizable markup.

In this endeavor he declared himself a failure. “I never did make no money bootlegging,” he said. “Every time I got ahold of any money, something’d happen, and I’d lose a bunch of whiskey or something, and just kept me poor as a church mouse, all the time.”

That’s not what the moonshiners believed. Most of Binion’s bootlegged corn liquor came from a network of stills hidden in the hardwood bottomlands of the Trinity River near Fairfield, ninety miles southeast of Dallas. Produced by Roger Young and his family, this whiskey even had a name: Freestone County Moonshine. The Youngs’ liquor was prized by drinkers for its potency and relative purity. It lacked adulterants such as lye, which caused a drinker’s lips to swell in terrible pain, and lead, which brought on the partial paralysis known as jake leg.

Though an average still could produce up to sixty gallons a week, the Youngs struggled to keep up with Binion’s growing business. On rare occasions when production ran ahead of demand, the Youngs wrapped gallon jugs of whiskey in burlap and buried them in a nearby cow pasture, a process they jokingly referred to as “aging.” With Binion as their primary cash customer, the Youngs became one of the wealthiest families in Freestone County. “They had more money down there than anybody,” a relative recalled. “They were rolling in money.”

Federal revenue agents generally did not present a problem, because the moonshiners bought off the county sheriff, who tipped them to impending raids. Bad weather, however, could shut down deliveries. Heavy rain turned the dirt roads of the bottomlands into impassable bogs, so the Youngs couldn’t get their liquor to the town of Corsicana, the usual rendezvous spot with Binion’s driver.

When the Youngs’ liquor wasn’t available, Binion bought Oklahoma hooch. “But the Oklahoma whiskey didn’t seem to be as good as the Freestone County whiskey,” Binion remembered. Other times, he trafficked in product smuggled from a real distillery, manufactured before Prohibition. “They had bonded whiskey, which cost more money to handle, and everything, and I never did too much of that. Just once in a while, I’d fool with a little bonded whiskey. But the bootlegging, to me, was never no good.”

Despite his disclaimers, Binion’s reputation among the illegal distilleries was that of a man of force and will. “Binion began to muscle in on whiskey operations,” a Dallas police report said, “and reportedly had gone into illegal whiskey plants and stated, ‘Everything that comes in between now and midnight is mine.’”

Raids and arrests happened infrequently, but they still presented a risk to Binion’s business. “Me and a guy by the name of Fat Harper, we got ahold of about $20,000 together, so we bought a lot of whiskey,” Binion recalled. They decided to keep some off the market in a warehouse owned by a man named Ward. “So we stored all this whiskey up in the warehouse when the weather was good to make a killing when the weather got bad and the whiskey’d go up.” But Ward fired an employee who got revenge by ratting to the police. “They came down there and arrested old man Ward and about thirteen people,” Binion said. “Didn’t get me and Fat, but we had to put up all the money to get them out. That whacked us out for sure.”

Even with the police mustering only occasional interest, Binion himself could not avoid arrest. “I got 60 days one time, and four months another time,” he said, though his record shows a $200 fine and a thirty-day sentence for violation of liquor laws.

After one collar for bootlegging, Binion faced up to five years in prison. But the judge was a friend of sorts. “I knew him and he knew me,” Binion said. “And he says, ‘You know, you’re supposed to go to the penitentiary.’ And I says, ‘Your honor,’ I said, ‘don’t sent me to the penitentiary,’ something to that effect. And he says, ‘Why?’ ‘Well,’ I says, ‘I’m not going to bootleg anymore.’” That wasn’t true, but it kept him out of the pen.

Beyond his bootlegging problems, Binion was in and out of other trouble in Dallas, but of minor consequence. In 1924 he was charged with tire theft, but not prosecuted. Later he was no-billed after a minor gambling arrest. A 1927 arrest for burglary and felony theft went unprosecuted. And a 1929 charge of aggravated assault was also dropped. That arrest appears to have stemmed from his reaction to a traffic accident in Dallas. As one of his sons told it much later, an unarmed Binion was attacked just after the wreck by more than a dozen men and—in a gladiatorial feat—ripped the bumper from his car and used it to defeat them one and all. “They kept coming,” son Ted said, “till there was fourteen of them with broken bones.” But the legend doesn’t quite match the facts, according to local newspaper reports, which said Binion used the damaged bumper from his car to strike just one person: the other driver, a middle-aged woman. For this, he became known to police as the Bumper Beater.

Because a large car part wasn’t always available, Binion usually employed more conventional protection. Dallas police twice arrested him as a young man for carrying concealed firearms—a pistol in one case, a sawed-off shotgun in another. The pistol got him sixty days.

• • •

The jail time didn’t stop him from carrying a gun. Having a piece in his pocket was an occupational necessity for a bootlegger, as Binion demonstrated on a warm, breezy October evening in 1931. He believed that another whiskey seller, a black man named Frank Bolding, had been stealing some of his liquor. The two of them met in the backyard of one of Binion’s safe houses, on Pocahontas Street in South Dallas, to talk the matter over.

“Me and him was sitting down on two boxes,” Binion recalled. “He was a bad bastard. So he done something I didn’t like and we was talking about it, and he jumped up right quick with a knife in his hand.”

The instinctive move for Binion would have been to jump up too. “Then he’d cut the shit out of me,” Binion said. “But I was a little smarter than that. I just fell backward off of that box and shot the sumbitch right there.”

Binion, in his later years, related other versions of the story. His son Ted told this one: “The guy hadn’t pulled the knife yet, even though he did have one . . . Dad felt like he was going to stab him.”

Whether or not the man brandished a blade, the result was indisputable: Bolding was shot in the throat. He fell to the ground, where he writhed and groaned. Binion stood over him and continued their discussion with, “I fooled you, didn’t I, you black son a bitch.” Neither Binion nor his crew sought a doctor for the wounded man, and within minutes he was dead.

Binion surrendered to authorities, claiming, “He come at me with a knife.” Even if that were false, a dead black bootlegger couldn’t excite much interest from the police, and it barely made the papers. Binion didn’t spend so much as a night in jail for the killing. Ultimately he pleaded guilty to murder, and received a two-year suspended sentence, allowing him to walk free. He probably could have escaped completely untouched by the courts had he pressed the matter. But the suspended sentence was a better bit of backscratching.

“I’ll tell you why,” he later said of his benign trip through the courthouse. “Bill McCraw was the district attorney. Me and him was goddamn good friends. He was gonna run for governor as DA. It looked kind of maybe bad if he’d just turned me loose . . . But I just—we just—decided I’d take a two-year suspended sentence to kind of make him look a little better, don’t you see, which we did.”

Not only was he a free man, Binion had a new nickname, thanks to his quick-draw dispatch of Bolding. Now everyone called him the Cowboy.

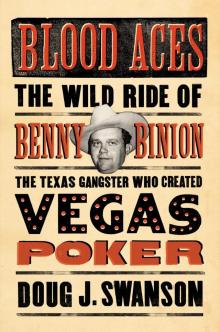

Benny Binion, an up-and-comer of Dallas vice, 1934.

3

PANCHO AND THE KLAN

Tough times make tough people.

—BB

Drinkers demanded a finished product, but suckers would pay for nothing but a chance. That’s why Binion considered liquor a mere stepping-stone. Soon he saw something that offered more promise than traffic in forbidden whiskey. He saw lucky numbers. “In about 1928 I opened up what they call a ‘policy,’” he said. This propelled him into a wider and more adventurous criminal world. And the profits were sensational.

The policy games were nothing more than simple lotteries in which players tried to pick three lucky digits. Each operator employed a team of runners, known as policy writers, who fanned out across town with sheets of numbers printed daily in red, green, and black. Players could bet a dime for a chance to win as much as $10. Winners were selected twice a day by the turning of the policy wheels. Some of the devices were actual spinning wheels, while others were small, rotating barrels from which the winning numbers were plucked. Operators set the odds and controlled the payouts, and applied the fix as necessary. It was a common practice for them to survey the bets, determine which numbers would make the house the most money, and maneuver to select those. With no oversight, they ensured their own handsome returns.

Policy operations stayed mobile to avoid raids and robberies. Not much equipment was needed—the wheel, a mimeograph to print tickets, and an adding machine to tally the proceeds. A game might spend time under bare lightbulbs in a sweltering room of a fleabag hotel before decamping to the smoky rear parlors of a side-street tavern. If operators got a tip that a raid was coming, they could pack up and be gone in minutes.

Though Binion had entered the policy business with some apprehension, it didn’t take long—about twelve hours—to see that he had strolled into a gold mine. “I started with fifty-six dollars,” he recalled. “The first day I made eight hundred dollars.” Even at its best, bootlegging never offered margins like that. A career was born.

• • •

Policy games operated under a strict racial structure: the owners were white and the customers were not. This represented a sizable base of potential gamblers; more than thirty thousand blacks now lived in Dallas. Some of them were descendants of the slaves brought to Texas to work the cotton fields before the Civil War. Others had fled the exhausted timberlands and spent farms of East Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas. They generally filled the low end of the employment scale, as porters, maids, elevator operators, dishwashers, and other common laborers. They took, in other words, jobs that whites would not do.

The white citizenry of Dallas tended to view the policy business with condescension and ridicule. “The policy game is mainly supported by Negroes to whom a $10.50 return on a 10-cent investment is big money,” the Dallas Morning News offered. The Daily Times Herald took it further in a front-page story that began this way: “‘Cullud folks jus’ gotta gamble—if’n they ain’t nothin’ else to bet on, they gonna bet on which way a bird fly when he leave off sittin’, so there you is.’ This, with a sheepish grin, constituted the most lucid answer the shambling Negro could give to a question which was asked ten of his race as they walked past city hall.”

The same story allowed the head of the Dallas police vice squad to offer his own theory. “Negroes just have to bet,” Captain Max Doughty said. “Their gambling instincts seem to be much more thoroughly developed than those of whites.” This ignored the fact that within a one-mile radius of the police station there were at least a dozen illegal dice rooms patronized by whites.

The captain’s attitude was hardly unusual. From its earliest days, Dallas had looked north in its moneyed aspirations and west in its frontier temperament. But in its race relations, it turned to the Old South. The town recorded its first lynchings in 1860, when three slaves were hanged after a raging fire destroyed most of the business district. It didn’t matter that no credible evidence linked the three men to the blaze. As one member of the Dallas “vigilance committee” explained, they were probably innocent but “somebody had to hang.” It could have been worse. Some of the vigilantes favored killing every black person in the county.

After the Civil War, and for the next nine decades, Dallas imposed stark segregation, with separate schools, health clinics, and parks. Municipal ordinances designated some neighborhoods white or Negro. At one point a city councilman proposed a law restricting Negro pedestrians to certain streets.

For the most part, blacks lived in the southern half of town, a squalid and—in low sections—flood-prone expanse of shanties lining unpaved roads. There were several handsome and well-tended neighborhoods of strivers and black professionals in southern Dallas, but they represented the exception. More than three-fourths of the dwellings in that part of the city were considered substandard. Most of those substandard houses had no running water. Half lacked gas or electricity. Fully one-fourth, a 1925 housing survey found, were “unfit for human habitation.” Segregation did allow one loophole: a few thousand Dallas blacks were permitted to live in wealthy white neighborhoods. They were the domestics who occupied the servants’ quarters of the well-to-do.

As was the case in many American cities, the Ku Klux Klan had a stranglehold on Dallas and its officials for much of the 1920s. A traveler stepping off a train at downtown’s Union Station might, if he timed it right, be greeted by the Klan’s fifty-member drum corps in white hoods and robes. For a time, the State Fair of Texas,

which was held in Dallas, observed an annual Klan Day. Many of the most powerful men in the city, from the police commissioner to influential clergy, were KKK members or supporters, which allowed the Klan to operate as it pleased. And it pleased the Klan to terrorize black people.

In 1921, a group of Klansmen grabbed a young black man from his home, put a rope around his neck, and drove him to a secluded spot south of town. The Klansmen did not lynch him. Instead, they whipped the man—twenty-five bloody lashes across his back with a bullwhip—and burned the letters KKK into his forehead with acid. Despite a detailed account of the attack published in the Times Herald, with the reporter as an eyewitness, authorities refused to investigate. “As I understand the case,” county sheriff Dan Harston, a Klansman, said, “the Negro was guilty of doing something which he had no right to do . . . He no doubt deserved it.” The man’s offense: a consensual liaison at the Adolphus Hotel with a white woman.

Nothing could incite the city’s passions like blacks killing whites, as seen when Lorenzo and Frank Noel were arrested in 1925 for a series of murders and rapes. The brothers were accused of attacking white couples parked in a lovers’ lane. Headlines called them the “Black Terrors.” As news of the Noels’ arrest spread, a crowd gathered outside the Dallas County Jail. By midnight, it had grown to a mob of five thousand. They threw bricks and rocks, and some tried to break through police lines and into the jail. Firemen blasted the rioters with water. When that didn’t work, deputies fired into the crowd, fatally wounding an eighteen-year-old white bystander. The mob was repulsed, and the brothers were later able to stand trial. A jury—all white—took two minutes to find them guilty, and they were executed about six weeks later.

Blood Aces

Blood Aces