- Home

- Doug Swanson

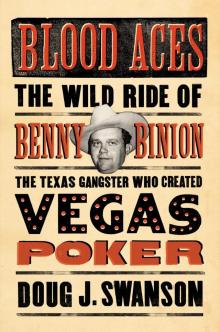

Blood Aces Page 18

Blood Aces Read online

Page 18

Another of Binion’s ardent advocates was Nevada’s senior senator, Pat McCarran. Like Binion, McCarran had spent much of his youth in the wild, herding livestock, although in McCarran’s case they were sheep. Starting small and local—the Nevada state assembly—McCarran built his political career brick by brick. He was not elected to the U.S. Senate until he was fifty-six. By turns sentimental and ruthless, he valued loyalty above all. In other words, he took care of his friends. He had intervened on behalf of Meyer Lansky and Bugsy Siegel so that they could procure scarce postwar construction materials for the building of the Flamingo, to the detriment of some deserving locals. Veterans home from the war couldn’t find bathtubs and basins for their new homes, but they could “see hundreds of them stacked up in the lot where the Flamingo was building,” Cahill recalled. And when Moe Dalitz faced some resistance in securing a gaming license in 1949, McCarran helped ease the way—after a meeting with Galveston mobster Sam Maceo, a Dalitz ally who had been Binion’s landlord at the Southland Hotel in Dallas.

Now that McCarran’s friend Binion needed help with his own license, the senator brought his considerable influence to bear. “McCarran never quit trying,” said Cahill, who recalled years later that the “McCarran machine” removed a Binion opponent from the tax commission by arranging for him to get a better-paying job at another state agency.

Such machinations were hardly secret at the time. An editorial in the Reno Evening Gazette took disapproving note of a “well-organized propaganda campaign” on Binion’s behalf. “Considerable pressure is being brought to bear on members of the tax commission,” the paper said. “To put it mildly, this is a rare and unusual performance.” That was a restrained way of saying what had become a general belief in the small world of Nevada casinos: the fix was in.

Before he could take advantage of that, Binion had to deal with the two inquiring lawmen from Texas.

• • •

On November 12, 1951, Butler and Crowder flew unannounced to Las Vegas and checked into a room at the Apache Hotel, one floor above the Horseshoe. When they learned that Binion couldn’t see them right away—he was home asleep—the pair took a walking tour of Fremont Street’s packed sidewalks. Glitter Gulch was enjoying record crowds that evening, thanks to Armistice Day celebrations. “The three-day holiday jammed the community to the gunwales,” the Review-Journal reported. By the time the two lawmen reached the bright lights of the Golden Nugget, across the street from the Horseshoe, a couple of Las Vegas police detectives were on their tail. Finally the detectives approached the Texans and asked if they were in town for business or pleasure. The conversation was an amicable one, but it also served to inform the outsiders that Binion owned the local cops.

The next morning Butler and Crowder met Binion for breakfast at his customary booth in the Horseshoe restaurant. He greeted the pair by half joking that he had heard Butler had come to kill him. With this gangster version of small talk out of the way, the two officers took their seats and began firing questions about Noble’s death. To judge from Binion’s demeanor, they could have been asking about the scrambled eggs. He was “cool and collected,” Butler and Crowder wrote in their report. “He seemed to be sure of himself, looked his questioner straight in the eye, and did not hesitate in his answers . . . Binion talked more freely than we expected him to.”

He also didn’t admit to any crime. The lawmen said numerous informants had told them that Binion stood behind the attempts on Noble’s life. Never happened, Binion said. If he had wanted Noble dead he could have found professional killers to do the job for a couple thousand bucks, five thousand at the most. Not that he knew any such killers. “He denied knowing any of the West Dallas punks that we have known to discuss Noble’s murder for money,” Butler and Crowder wrote.

Well, he did know some of them. Binion acknowledged more than a passing acquaintance with Johnny Grisaffi and the departed Lois Green. This prompted Butler to recall a night when he stopped Green as he drove through Dallas. Green “jumped out of the car with a pistol,” in Butler’s account, but threw it down when he saw who had pulled him over. Green told Butler he was upset and anxious because of his failed attempts to dispatch the Cat, but that Binion was going to give him “all the time I need” to kill Noble. The anecdote caused Binion to stare in surprise. “Did that son of a bitch really say that?” he asked.

Next came more conversational pleasantries. Binion told them he had a new bodyguard, one Cole Agee, a former border patrolman and a crack shot. “He can knock the eyes out of a gnat,” he bragged. He also announced that he had personally made “over a million dollars” since moving to Nevada, and that he had ten thousand acres of oil-producing land under lease in Wyoming. “He had paid 25 cents an acre for the lease and had just turned down $3.50 an acre for it,” the lawmen’s report noted.

When Butler and Crowder asked him about the recent shots fired at his car in Las Vegas, Binion laughed it off. Although he had previously denied it, he now dismissed the incident as little more than a prank, a bit of spirited recreation by some carousing soldiers or liquored-up cowboys. The two experienced investigators heard this fanciful tale from a racketeer who had been locked in a violent feud and swallowed it whole. “After this description by Binion,” Crowder and Butler wrote, “we were inclined to agree with him.”

Next they talked about control of the Horseshoe, and Binion’s partnership charade with Monte Bernstein. For one of the few times in the interview, Binion turned candid. “He contended that his relations with the Jew were strictly business,” the lawmen wrote. “It was clear that Binion ran the place.”

And that was that. Two hotshot lawmen finally scored an interview with the notorious chieftain, the fugitive from justice, the prime suspect in a spectacular murder, and they came away empty. Over the course of several hours, Binion had evaded, dissembled, and denied, all while giving his questioners almost nothing in the way of actionable information.

Butler and Crowder couldn’t get a flight out that afternoon. So Binion arranged for one of his favorite local lawmen to take his Texas counterparts on an after-dark excursion to the Strip. “That evening, Captain Ralph Lamb of the Las Vegas Sheriff’s Department entertained us at the Flamingo Club,” they wrote in their report. They didn’t mention that the Flamingo remained one of the most mobbed-up casinos in town.

At least they had an escort who knew the ins and outs of Vegas. Lamb was, in Binion’s estimation, “as fine a man as I ever seen.” When Crowder and Butler met him, he had embarked on a long law enforcement career that would include years of taking thousands of dollars in cash under the table from Binion.

The two Texas investigators encountered another local cop luminary as well. “We met Sheriff Glen Jones, who was having breakfast at the Horseshoe Club,” they wrote. The sheriff was in fact a regular at Binion’s restaurant, where he ate for free, at least until his law enforcement career expired prematurely. Within a few years he would be caught in a sting operation and accused of extorting $1,000 a month in protection money from Roxie’s, a brothel operating out of a motel on the Boulder Highway.

“A good man, Glen Jones,” Binion said later. “But he drank a little whiskey, and they got him tangled up.”

A Horseshoe postcard from the 1950s touting a new sort of tourist attraction.

15

“THEY WAS ON THE TAKE”

Them dice just run in cycles.

—BB

If Las Vegas in the summer was a suburb of hell, albeit one with nearly naked chorus girls and all-you-can-eat buffets, the weeks of late autumn came close to compensating for the deadly heat. The nights dipped into a pleasant chill and the afternoons rolled in cool and dry, with a high, clear sky. Perfect weather for setting off some A-bombs.

In November 1951, after concluding a series of blasts, the federal government announced that it would soon resume the testing of atomic weapons at Frenchman Flat and Yucca Flat,

a couple of forsaken patches of the Mojave sixty-five miles northwest of Las Vegas. The first of the bombs had been detonated ten months before at the Nevada Test Site, and the feds had been pleased with the results. The military and the scientists considered the test site a logistical godsend—isolated but accessible, reachable by road and rail but suitably far from prying eyes. Having such a proving ground on U.S. soil was “one of the best things that has happened to us,” said Gordon Dean, chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission.

On the days that bombs went off, the Vegas gambler or tourist who timed it right could look to the horizon and see the remnants of a pinkish mushroom cloud against the cobalt-blue sky. Some casinos, including the Horseshoe, put pictures of the clouds on promotional postcards. Other clubs offered special “atomic cocktails” and detonation-watching parties from rooftops. A dancer at the Last Frontier performed as Miss Atomic Blast, described by a canny publicity agent as “radiating loveliness instead of deadly atomic particles.”

Luckily for Las Vegas, the prevailing winds were westerly, as they swept the detonations’ floating, irradiated dust and ash away from the city and over the scattered sheep ranchers, desert dwellers, and polygamists of eastern Nevada and Utah—unsuspecting people referred to in federal government documents of the time as “a low-use segment of the population.” The radiation would do its work on them, but that would take a while. Not for years would hundreds of people, later known as downwinders, be diagnosed with cancers blamed on the fallout.

For now, Vegas welcomed the news that the tests would be starting again, because activity at the test site meant even more jobs for locals. These were the years when the city’s economy seemed to hum. In addition to military spending, tourist numbers had been growing, and construction of resort casinos along the Strip continued apace. The Sahara was going up, with the $5.5 million Sands soon to follow. Coming next: the Showboat and the Riviera.

Even more developers with grand plans were descending on Las Vegas, for there were fortunes to be made. Hence Binion’s urgency. Although the Horseshoe was doing red-hot business, he couldn’t maintain the shotgun marriage with Monte Bernstein much longer. To really make this deal work the way he wanted, Binion needed his license.

• • •

On the Strip, bandleader Harry James and his wife, actress Betty Grable, were arm in arm, exuding furs-and-diamonds glamour at the Thunderbird. Back on Fremont, the Horseshoe continued to pull in the crowds night after night, and proclaimed its simple slogan in quarter-page newspaper ads: “Always Action.” But on the morning of December 1, 1951, the real action could be found one block from the Horseshoe, at the federal building on Stewart Avenue, where the state tax commission had gathered for a hearing on Binion’s license application. This was the same place where the Kefauver committee had gathered a year earlier. But this time Binion showed up, ready to make his pitch.

He strolled into the second-floor hallway about eleven thirty that morning, the heels of his handmade Willie Lusk boots knocking against the brown terrazzo floor. Binion waved to half a dozen newsmen as he ambled past four armed Nevada highway patrolmen, who were there to keep irate reporters and curious citizens out of the hearing. For the star witness, the padded leather doors, the color of port wine, opened wide. Inside the high-ceilinged courtroom, where the meeting was chaired by Governor Russell, Binion settled himself into a shiny wooden chair and—surrounded by twenty bas-relief eagles along the top of all four walls—wasted no time in turning on the ranch-house charm. “Binion had this very engaging style,” said Robbins Cahill, then the commission’s secretary.

Upon swearing to tell the truth, Binion first had to explain his shooting of Ben Freiden, the rival numbers operator, which he did with ease. “He was a bad man, a very bad man,” he said. This not only satisfied the concerns of his questioners but also entertained them. Recalled Cahill, “He had the tax commission in stitches, just laughing at his killing a man.” Next Binion justified his shooting of Frank Bolding, the bootlegger. “Just a nigger I caught stealing some whiskey,” he said. Again laughter erupted. And so it went, for about an hour.

After Binion left the hearing, state senator E. L. Nores made an appearance. Whether he drove his new Hudson Hornet to the courthouse is unclear, but his support for Binion hit a familiar blaring note. “Binion is a man you can believe in,” he said. “I have business dealings with him and have found him to be a man of high character.” As to problems in Texas, Nores remained untroubled. The senator said he had a brother in Dallas who had assured him that Binion had a good reputation there. Nores offered no proof of his brother’s investigative credentials; mere siblinghood was apparently sufficient. If his friend did not get a casino license, Nores told commissioners, “you are making a serious mistake.”

That afternoon, they voted unanimously to approve Binion’s application. (Cahill did not have a vote.) The commissioners did add a probationary requirement: if Binion were to “bring discredit on himself or the state of Nevada,” the license would be revoked. Absent that, he was free to run the Horseshoe.

This represented a remarkable turnaround, even in a state known for creative approaches to regulation. While an ebullient Binion was slapping backs around his casino tables, the Reno Evening Gazette again shifted into high dudgeon. “Taking on extraordinary powers,” the Gazette said in an editorial, “the Nevada tax commission in effect held a trial and granted an acquittal on a Texas criminal indictment, and overrode the charges of the Kefauver crime investigating committee.” The paper also reminded readers that Binion “is still a fugitive from justice in the eyes of Texas law, and it is not likely that any other state but Nevada would grant him asylum.”

A second Gazette editorial-page column piled on: “Maybe Binion’s qualifications, reputation and past records were all carefully scrutinized by members of the tax commission, but if such was the case, the members and [Governor] Russell must have been benignly blind-folded at the time.”

Binion—for once—kept his immediate public reaction truthful, concise, and diplomatic. “I am,” he said of the licensing, “very thankful.”

Years later, he was asked how he had swayed the commission. “They was on the take,” he said. “There would’ve been some you could’ve bribed, if you’d wanted to, but I wouldn’t give ’em nothing.” This was in all likelihood another of his classic semantic denials, the Cowboy once again regarding payoffs as friendly gifts and painting stark corruption as beneficence. In contrast, a 1953 FBI report contained this blunt summation: “Reports were received from reliable Informants in the Las Vegas area that Benny Binion ‘really put out’ to the commissioners of the Nevada State Tax Commission.”

• • •

Whatever it cost, it was worth it. Binion had risen so high now that within a few weeks he even made Walter Winchell’s “On Broadway” newspaper column. From Manhattan, Winchell presided as the master of the snappy three-dot gossip dispatch. (“. . . Imogene Coca back from a Cuban holiday with a cocoa-tan . . .”) He dished out a frantic mix of celebrity news, political bulletins, and quick-release anecdotes, some of which might have been true.

“A wealthy Texan named Blondy Turner was in New York recently,” Winchell wrote in his year-end column for 1951. “He telephoned Benny Binion, prop of the Horseshoe, the newest gambling palace in Las Vegas, to wish him good luck.” Blondy Turner placed a $10,000 dice bet with Binion over the phone, Winchell said, and Binion held the receiver close enough to the craps table that Blondy in New York could hear the stickman call his victory. Winchell continued: “‘You win Ten Big Ones!’ cheerfully informed Mr. Binion over the Long-Distance . . . ‘Okay,’ chuckled Blondy Turner in Manhattan. ‘See you next week to collect it!’ . . . When Mr. Turner, the Sportsman, arrived in Vegas, he made straight for the dice table . . . And lost $200,000.”

In Vegas, even the fables were going Benny’s way.

• • •

Life at the estate on Bonanza R

oad approached the idyllic, Vegas version. The Binion compound served as a mini-ranch and perpetual summer camp for the Binion children and their friends. They had a concrete swimming pool behind the house, and plenty of room among the groves of Chinese elms for them to ride horses with Gold Dollar.

Binion, as always, made it home for dinner most nights. Over a feast of, say, fried frog legs, he went around the table to each child, asking for thoughts on the day. “We could talk about anything, except we couldn’t have any arguments,” daughter Brenda recalled, which meant that one contentious subject—on which everyone had strong opinions—was off-limits. “We couldn’t talk about horses.”

With his two Cadillacs parked out front, Binion sat on a net worth that easily exceeded $2 million. The ranch in Montana alone was worth at least $722,000, and it supported a thousand head of cattle. And there were the oil leases he had mentioned to the Texas cops.

But the real gusher was the Horseshoe, where the cash money flowed seven days a week. Binion was forty-seven years old now, with nearly three decades of running gambling joints behind him, and he had made the most of his experience. Believing as always in loyalty, he had surrounded himself at the Horseshoe with trusted associates from his Texas days. As resistance from other casino owners had faded, he incorporated a primary lesson from his Dallas mentor Warren Diamond. He took the biggest bets, because the more the customers could bet, the more they could lose.

Other casinos imposed ceilings on craps bets to contain their own short-term loss exposure. But the Horseshoe was different, and ultimately this became Binion’s Vegas trademark: the craps player’s first bet, no matter how high, was his limit. A customer could put down a cool million if he had the guts and the cash. This appealed both to the fantasies of the casual gambler and the strategies of the high roller, and let a Wild West ethos blow through the room. It wasn’t long before the Horseshoe was considered the center of the craps universe.

Blood Aces

Blood Aces